Research

The Youth Sleep Crisis: As tech has been increasing, so has insufficient sleep for kids and teens. Much of this problem is due to screens in the bedroom during bedtime.

Listed below are key research findings, all of which involve children and/or teenagers.

1. Decline in sleep of children and teens

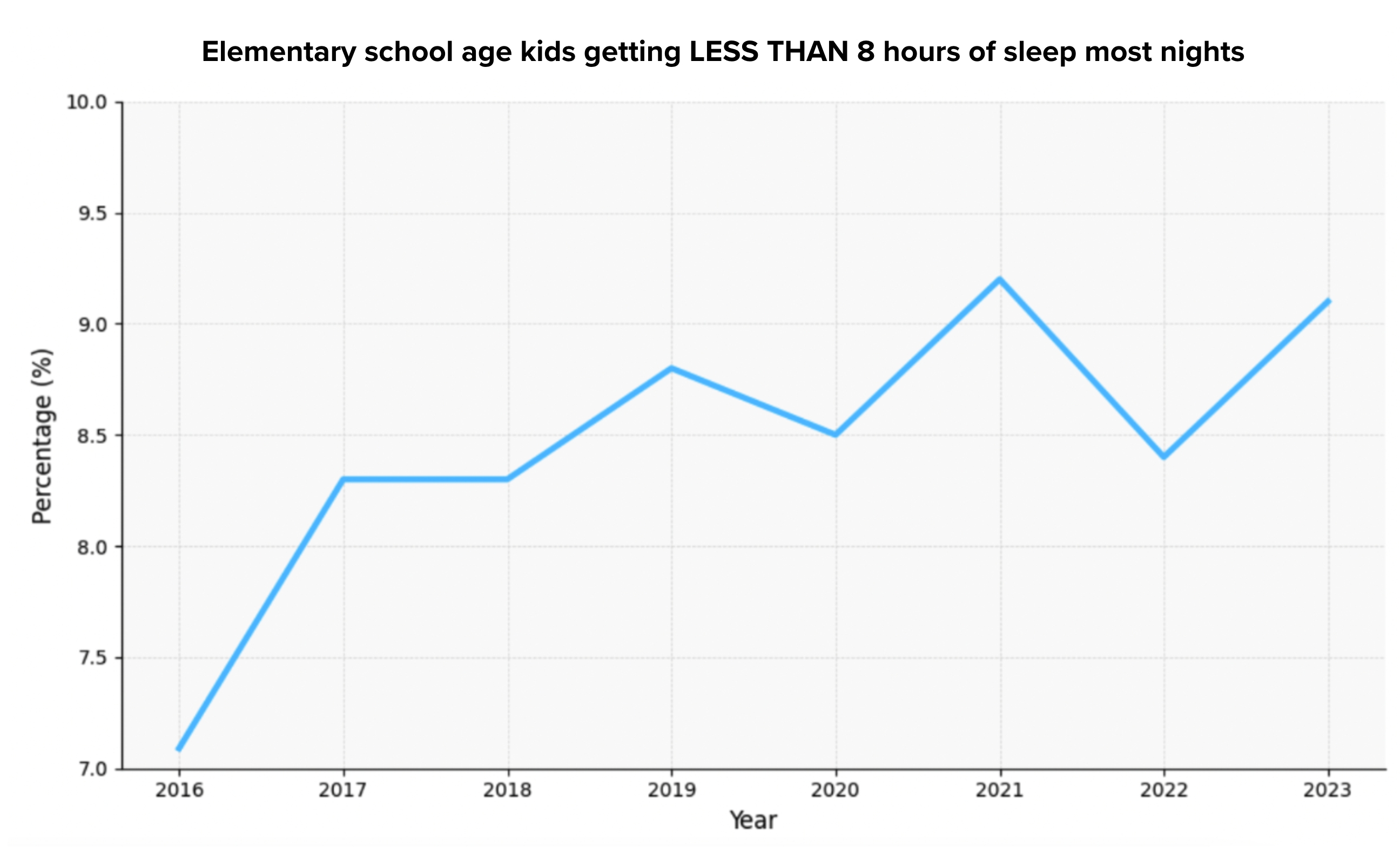

Data on children (ages 5 to 12)

Despite the 9–12 hour sleep recommendation for this age group, millions of children fall short.

Approximately 2.7 million children get less than 8 hours of sleep most nights.

Of note, it is not just sleep quantity that has suffered, but sleep quality as well.

*2016 was the first year they started to measure this and 2023 is the most current published data.

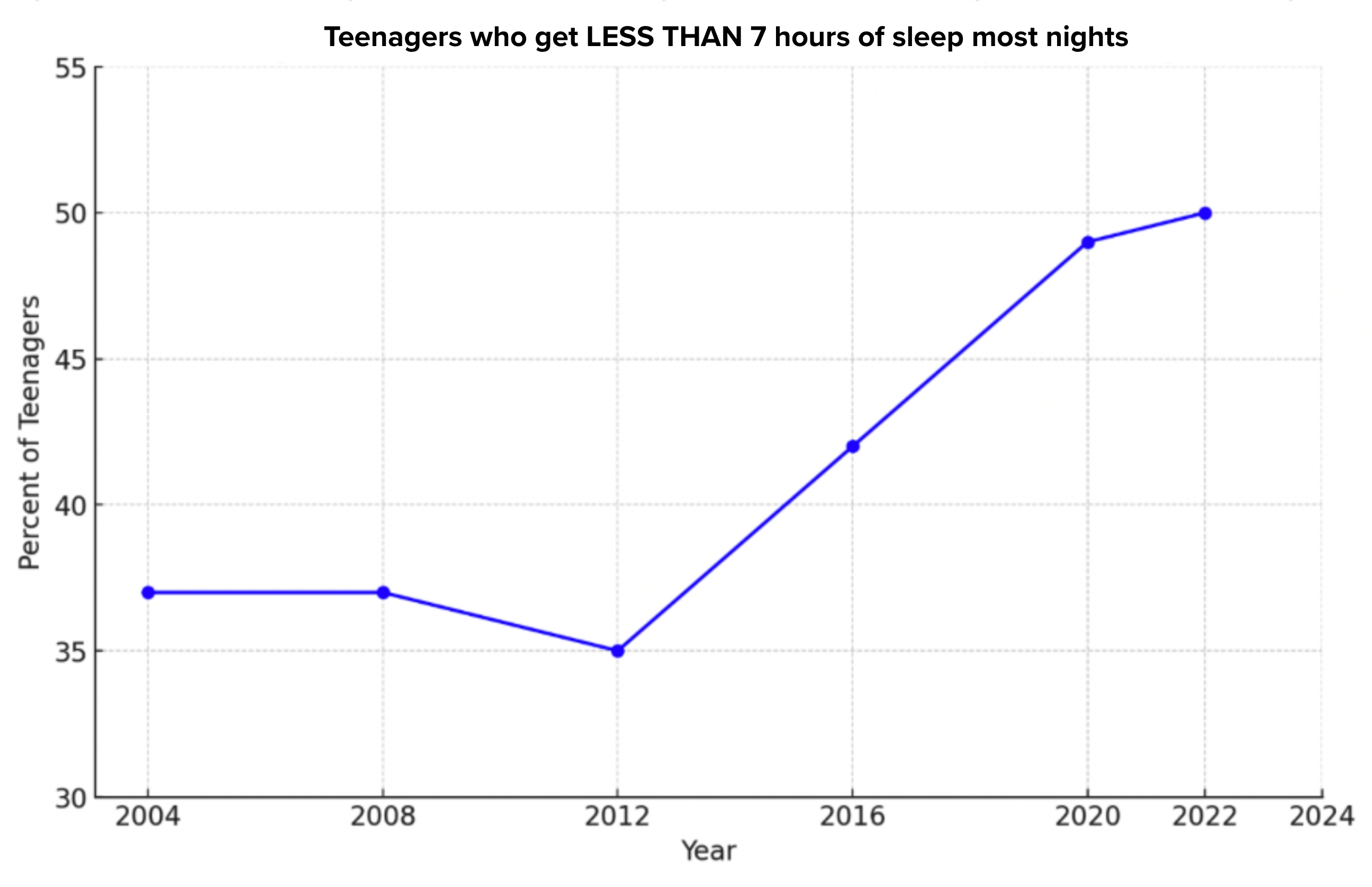

Data on teenagers (ages 13 to 18)

Despite recommendations for 8–10 hours of nightly sleep, an increasing number of teens fall short.

In fact nearly 13 million* teens are getting less than 7 hours of sleep most nights.

(*calculated using 2024 census data and Monitoring The Future data)

2. Screens in bedrooms during sleep time hurts sleep

The New Normal: Parents, Teens, Screens & Sleep in The United States

Key Findings: 36% of teens wake up at least once during the night to check their device. 70% of teens bring their device to bed or keep it within reach under the covers. 40% of teens say they would get more sleep if their phone were not in their bedroom.

Ref: Common Sense Media (2019)

A new public health challenge? A novel study design based on high-resolution smartphone data

Key Findings: Many adolescents experience sleep interruptions from smartphone use. More frequent interruptions were linked to shorter overall sleep duration.

Ref: Rod et al. (2016), PLOS ONE.

Association Between Portable Screen-Based Media Device Access or Use and Sleep Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Key Findings: Across 20 studies involving over 125,000 children (average age 14.5 years), bedtime access to media devices such as smartphones and tablets was associated with a higher risk of insufficient sleep, poorer sleep quality, and increased daytime sleepiness. Even having a device in the bedroom without using it was linked to worse sleep outcomes.

Ref: Carter et al. (2016), JAMA Pediatrics.

Impact of Adolescents’ Screen Time and Nocturnal Mobile Phone-Related Awakenings on Sleep and General Health Symptoms: A Prospective Cohort Study

Key Finding: A longitudinal study of over 800 adolescents found that those experiencing mobile phone-related awakenings at night were 3.5 times more likely to develop difficulties falling asleep and 5.4 times more likely to experience restless sleep over one year.

Ref: Foerster et al. (2019), Sleep Health.

Life in Media Survey: A Baseline Study of Digital Media Use and Well-being Among 11- to 13-year-olds

Key Findings: Among 1,510 Florida youth ages 11–13, 78% own a smartphone; of these, 72% keep it in their bedroom at night. One in four of those would sleep with it in hand. These youth average 49 minutes less sleep per night than peers who leave their phone in another room.

Ref: Martin et al. (2025) Life in Media Survey.

Survey on Factors Affecting Kids’ Sleep

Key Finding: In a national parent survey, video gaming ranked as the top perceived cause of poor sleep in children and teens. Half of parents (50%) said video games negatively affect their child’s sleep schedule, compared to only one-third (34%) who cited homework.

Ref: Sleep Foundation (2023), Sleep in America Poll.

Smartphone Ownership, Age of Smartphone Acquisition, and Health Outcomes in Early Adolescence

Key Finding: Children who owned a smartphone by age 12 had significantly higher odds of insufficient sleep compared with peers who did not yet own a smartphone, highlighting early smartphone access as a risk factor for sleep loss in adolescence.

Ref: Barzilay et al. (2025). Pediatrics.

3. Problems with insufficient sleep

a) Brain Development

Effects of Sleep Duration on Neurocognitive Development in Early Adolescents in the USA: A Propensity Score Matched, Longitudinal, Observational Study

Key Finding: Insufficient sleep over time is linked to reduced gray matter volume in several key brain regions and disrupted functional connectivity, especially in networks essential for cognitive and emotional regulation.

Ref: Wang et al. (2022), The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

Relations Between Sleep Patterns Early in Life and Brain Development: A Review

Key Finding: This comprehensive review highlights that sleep plays a crucial role in modulating brain structure and neural activity throughout childhood; during development, changes in sleep physiology parallel and influence brain maturation.

Ref: Lokhandwala et al. (2022), PubMed Review Article

The Importance of Sleep for the Developing Brain

Key Findings: Emerging research spanning changes in sleep behavior and brain physiology suggests sleep plays a critical role in brain development, including associations between slow-wave activity, myelin formation, hippocampal growth, and broader functional connectivity in developing neural networks.

Ref: Riggins et al. (2024), Current Sleep Medicine Reports

A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid

Key Finding: The study showed for the first time that sleep activates a brain-wide waste-clearance system that is up to ten times more active than when awake, helping remove toxic metabolic by-products from the brain, including amyloid-beta linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

Ref: Nedergaard et al. (2012). Science Translational Medicine.

Age-Related Change of Glymphatic Function in Normative Children Assessed Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging–Analysis Along the Perivascular Space

Key Finding: The study found that glymphatic function changes with age throughout childhood, indicating that the brain’s waste-clearance system continues to develop during the pediatric years rather than being fully mature early in life.

Ref: Wong et al. (2025). Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

b) Mental and Emotional Health

Sleepless in Fairfax: The Difference One More Hour of Sleep Can Make for Teen Hopelessness, Suicidal Ideation, and Substance Use

Key Findings: Among high school students, each hour less of sleep was associated with a 38% higher likelihood of feeling hopeless, a 42% increase in suicidal ideation, and a 23% greater risk of substance use.

Ref: Dudovitz et al, (2024), Sleep Health.

Trajectories of Sleep Problems in Childhood: Associations with Mental Health in Adolescence

Key Findings: Sleep problems in earlier childhood predict poorer mental health in later adolescence. Youth with persistent sleep problems from ages 9–11 showed higher levels of externalizing behavior, depressive symptoms, and anxiety at age 18.

Ref: Matricciani et al. (2023), SLEEP, Oxford Academic.

Sleep Mediates the Association Between Adolescent Screen Time and Depressive Symptoms

Key Findings: Increased screen time was linked to 26% more frequent problems falling asleep, 23% more frequent problems staying asleep, and a 5% reduction in weekday sleep duration. The relationship between activities such as social messaging, web surfing, and TV watching and depressive symptoms was fully explained by their impact on sleep. For gaming, sleep problems partially explained the relationship, accounting for 38.5% of the link.

Ref: Lemola et al. (2015), Journal of Adolescence.

c) Social Life

The Social Side of Sleep: A Systematic Review of the Longitudinal Associations Between Peer Relationships and Sleep Quality

Key Findings: Negative peer relationships, such as bullying and cyberbullying, were linked to a 22% increase in sleep disturbances over time, while poor sleep quality was associated with a 19% higher risk of negative peer interactions. These findings suggest a bidirectional relationship between sleep and social experiences.

Ref: Becker et al. (2021), Sleep Health.

The Role of Poor Sleep on the Development of Self-Control and Antisocial Behavior from Adolescence to Adulthood

Key Findings: Among individuals aged 16 to 27, increases in poor sleep quality amplified the link between sensation-seeking and antisocial behavior. Changes in sleep were also associated with changes in impulsivity and sensation seeking, suggesting a reciprocal dynamic over time.

Ref: Connolly et al. (2022), Journal of Criminal Justice.

d) Learning, Attention & Academics

Sleep Insufficiency, Sleep Health Problems and Performance in High School Students

Key Findings: High school students who slept less than 7 hours on both weekdays and weekends were 1.66 times more likely to report grades of "C or worse" compared to peers with more sleep. Those with night awakenings were 1.39 times more likely to have poorer school performance, and students with prolonged sleep onset were 2.35 times more likely to report lower grades.

Ref: Lo et al. (2016), Nature and Science of Sleep.

Impact of Multi-Night Experimentally Induced Short Sleep on Adolescent Performance in a Simulated Classroom

Key Findings: In an experimental study, adolescents subjected to shortened sleep (6.5 hours in bed for multiple nights) scored lower on a quiz in a simulated classroom environment, exhibited diminished learning, displayed increased inattention, and experienced heightened sleepiness.

Ref: Beebe et al. (2017), Sleep.

Reducing the Use of Screen Electronic Devices in the Evening Is Associated with Improved Sleep and Daytime Vigilance in Adolescents

Key Findings: Limiting screen use after 9:00 pm helped adolescents fall asleep earlier, increased their total sleep time on school nights, and enhanced daytime vigilance, as shown by quicker reaction times on attention tasks.

Ref: Perrault et al. (2019), Sleep.

Nightly Sleep Duration Predicts Grade Point Average in the First Year of College

Key Findings: First-year college students averaged only 6 hours and 37 minutes of sleep per night. Those who achieved longer average nightly sleep durations early in the term had higher end-of-term GPAs, with each additional hour of sleep linked to a 0.07-point increase in GPA. Receiving less than 6 hours of sleep was associated with a significant decline in academic performance.

Ref: Creswell et al. (2023), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sleep Quality, Duration, and Consistency Are Associated with Better Academic Performance in College Students

Key Findings: College students who consistently slept for at least 7 hours per night achieved better grades than those who slept less than 7 hours. Differences in sleep duration accounted for nearly one-fourth of the variation in grade differences.

Ref: Okano et al. (2019), npj Science of Learning.

e) Negative Risk-Taking Behaviors

Association Between Short Sleep Duration and Risk Behavior Factors in Middle School Students

Key Findings: Middle schoolers sleeping less than 7 hours per night had higher odds of risk behaviors, including substance use, antisocial attitudes, and sensation-seeking, with a clear dose–response relationship.

Ref: Owens et al. (2017), Sleep.

Dose-Dependent Associations Between Sleep Duration and Unsafe Behaviors Among US High School Students

Key Findings: Analysis of data from 67,615 U.S. high schoolers (2007–2015) found that fewer nightly sleep hours were linked in a dose-dependent manner to higher odds of risky driving, substance use, risky sexual activity, aggression, poor mood, and self-harm. Sleeping less than 6 hours was associated with triple the odds of considering, planning, or attempting suicide, and quadruple the odds of an attempt requiring medical care compared to sleeping 8+ hours.

Ref: Wheaton et al. (2018), JAMA Pediatrics.

Take the pledge!

I pledge YES to keep devices out of my child’s bedroom for sleep time